Disagreeing about God is easy. If we are going to make headway in our

conversations about God, however, we’d do well to focus first on our common

ground. At the risk of getting abstract

and boring: Suppose Smith and Jones

disagree about matter p. And suppose that

S and J are both reasonable, thoughtful people with the intention of getting

their beliefs to align as well as they can with the facts and the canons of inductive

and deductive reasoning. Smith will have

one body of information that Smith takes to be relevant to deciding the issue

and Jones will most likely have another.

There will no doubt be some overlap between, but the disagree is often

related to different pieces of information in those two bodies of

evidence. Smith and Jones need to share evidence, and come to some

agreement about what the complete list of facts are regarding p, or at least

the most complete list that they can acquire.

The disciplines of physics, astronomy, cosmology,

anthropology, biology, psychology have converged on this short summary of the

history of everything. A staggering and unsurpassed amount of work, critical

reasoning, skeptical scrutiny, vetting, and aggressive efforts at

disconfirmation that have gone into justifying this account of the history of

everything. That is, the story is the

result of the greatest minds in human history using our best methods for

investigating the world.

The arguments that one might make for some other version of

events, or the evidence that one might cite to justify a contrary picture of

reality, are all inferior. To prefer one

of those alternative accounts of reality is, plainly stated, flagrantly

irrational.

So discussions about God need to start with this bit of

evidence sharing as their starting point.

Here’s a summary of what we know about the universe, the

Earth, life, humanity, and evolution.

Approximately

13.7 billion years ago, the universe went from a singularity state of infinite

curvature and energy to a rapidly expanding chaotic state, the Big Bang. During the first pico and nano seconds of

this period of rapid expansion, the types and behavior of particles that

existed rapidly change as the energy levels dropped. Within a few nanoseconds, the kinds of matter

and the ways they behave settled into, more or less, the sorts of material

constituents we find today. At this

point, only hydrogen, helium, and lithium exist. The matter continues to expand outward and eventually,

several billion years later, gravitational pull congregates clumps of matter

together to form stars. These heat and

energy at the cores of these stars cook the early forms of matter, transforming

it and creating many of the other, heavier elements on the periodic table. Some of these stars are of sufficient mass to

ultimately collapse on themselves, exploding outward and spraying the new elements

formed in their cores out into space.

That matter eventually coalesces into smaller stars, planets and moons

like our own.

The Earth formed

about 4.5 billion years ago. Simple, self-replicating molecules appear on

Earth around 4 billion years ago (abiogenesis).

Once there is replication, natural selection and random mutations over

billions of years lead to the evolution of more and more life forms, many of

them of increasing levels of complexity.

The dinosaurs emerge from this

process. The Triassic, Jurassic,

and Cretaceous periods range from about 208 million years ago to 65 million

years ago. There are boom and bust cycles

of rapid proliferations of life (e.g. Cambrian explosion) and mass extinctions,

such as the asteroid event that we think was responsible for the extinction of

the dinosaurs. The ecological gap left

by the dinosaurs provides the opportunity for placental mammals to expand and

diversify.

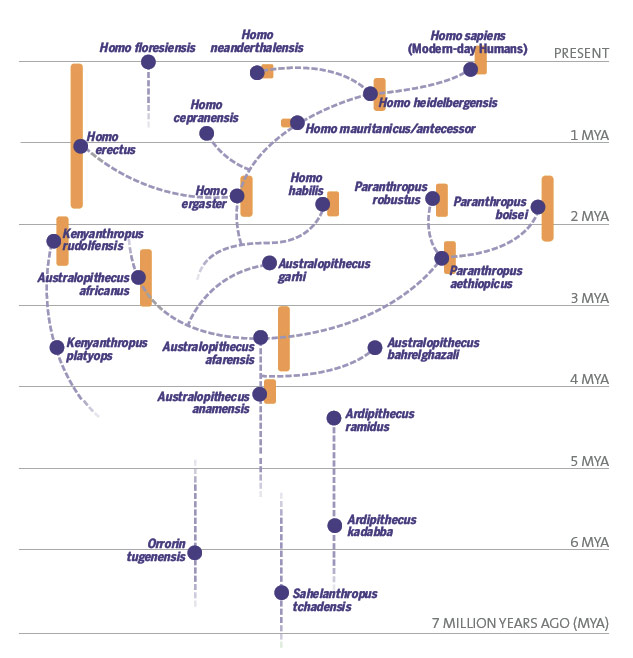

The earliest known stone tools originate with hominids 2.5 to 2.6 million years ago. Estimates about the emergence of language range from 5 million years ago to 100,000 years ago. Modern humans (homo

sapiens) originated in Africa about 200,000 years ago, 60 million

years after the dinosaurs have gone extinct.

A variety of early hominid groups vie for survival until all related

lines except homo sapiens are extinct. We

are still piecing together many of the connections and relationships between

these species.

There

is evidence of human religious behavior such as burial rituals dating back

approximately 300,000 years.

Only very recently have one of the hominid species--homo sapiens--on the planet developed cognitive faculties that were sophisticated enough to be able to discover these various facts about the universe. Some of those discoveries are landmarks of vast significance in our develop, although not in a cosmic scale: Darwin’s The Origin of Species is published in 1859. In 1929, Edwin Hubble published his paper, “A Relation

Between Distance and Radial Velocity Among Extra-Galactic Nebulae,” in which he

showed that the universe is expanding.

Extrapolating backward from its rate of expansion made it possible to

date the explosive beginning of the universe at approximately 13.7 billion

years ago. In 1953, James D. Watson and Francis Crick published their

discovery of DNA in Nature: “A Structure

of Deoxyrobose Nucleic Acid.”

Sharing Evidence

Now

it seems to me that any religious doctrine that portends to give an accurate account

of the nature of the universe, the origins of the universe, the existence and

development of life, the origins of humanity, or the relationship between

humanity and the rest of the cosmos must, at the very least, accord with this

history of everything. If a religious

account of the world presents us with different details about the order, span,

or nature of these events, then we must conclude that is it mistaken. 4 in 10 Americans are young Earth

creationists

http://www.gallup.com/poll/145286/four-americans-believe-strict-creationism.aspx where young Earth creationism is the view the

universe, the Earth, and all life on Earth were created in their more or less

present forms within the last 10,000 years.

So that 40% of the population believe a number of things that are flatly

disproven by our best evidence and scientific work. (The oft repeated claim that religious views

and science are perfectly consistent or compatible is also plainly false in

this light.)

Responsible

and mature discussions about God should start with this mutually agreed upon

list of basics about the universe we inhabit.

Denying these basics, given the quantity and quality of evidence we have

in their favor, is irrational and irresponsible. Someone who would deny the basics is either

grossly misinformed, or perhaps he is more committed to the religious ideology

than to believing that which is reasonable and best supported by the

evidence.

- The Big Bang occurred 13.7 billion years ago.

- Only hydrogen, helium, and lithium exist for millions of years

until large stars form and create many of the other, heavier elements on the periodic

table.

- Some of these stars go supernova and distribute these new elements

into space.

- That matter eventually coalesces into smaller stars, planets and

moons like our own.

- The Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago.

- Life in the form of the simplest, self-replicating molecules

occurs on Earth around 4 billion years ago.

- Once there is replication, natural selection and random mutations over

billions of years lead to the evolution of more and more life forms, many of

them of increasing levels of complexity.

- Dinosaurs live from about 208 million years ago to 65 million

years ago.

- Life on the planet goes through several mass extinctions.

- The Cambrian explosion—a rapid proliferation of the kinds and

numbers of living organisms on the planet, occurs about 540 million years ago.

- Mammals begin to expand and diversify significantly about 54

million years ago.

- Modern humans (homo sapiens) originated in Africa

about 200,000 years ago.

- Human religious behavior starts approximately 300,000 years ago.

12 comments:

I would like to add: that if one believes things contrary to any, well supported, scientific theory, one is responsible to provide an explanation of said belief that incorporates everything else we already know about the universe. In other words, there must be a replacement theory that explains the phenomenon better than the current theory.

You state -

Modern humans (homo sapiens) originated in Africa about 200,000 years ago.

Human religious behavior starts approximately 300,000 years ago.

I'm taking it that you meant 30,000 years ago ... or do you have evidence of religious behaviour by earlier homo 'whatever'?

There are several "Human" species in ancient history, but the modern (our) "Human" species is homo sapien.

Clearly I'm aware of that. What I'm not aware of is evidence of religious practice among earlier hominids. Hence my wondering if an extra 0 had been added by accident.

Some more milestones I want to add to this list:

Sudden expansion of early hominid brain size: 800,000 to 200,000 years ago.

Emergence of human languages, approx. 100,000 years ago.

"S and J are both reasonable, thoughtful people...Smith and Jones need to share evidence."

Surprisingly, that's not necessary: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aumann's_agreement_theorem

Thanks Brian. But I don't see anything in this brief description of Aumann's theorem that runs contrary to what I've said. If Smith and Jones are concerned to make progress on their disagreement, and if they are motivated to find the one, best justified conclusion, then they need to share their evidence. If you know something I don't about God, I want to hear it so that my considerations can be as comprehensive as possible. Your link says: "Aumann's agreement theorem says that two people acting rationally (in a certain precise sense) and with common knowledge of each other's beliefs cannot agree to disagree. More specifically, if two people are genuine Bayesian rationalists with common priors, and if they each have common knowledge of their individual posteriors, then their posteriors must be equal." That seems right to me. After they have concurred on the same, relevant body of evidence, S and J cannot conclude about the other that he is being reasonable AND that he believes the opposite of me. Feldman calls it the Uniqueness Condition. There is one and only one conclusion justified by any body of evidence when the cannons of inductive and deductive logic are applied to it. So if Smith and I disagree after sharing info, then I have to conclude that one of us is not being rational--he's either made a mistake, a fallacy, misapplied a rule of inference, or otherwise not been ideally rational. Feldman says we should both suspend judgment in this circumstance.

"After they have concurred on the same, relevant body of evidence, S and J cannot conclude about the other that he is being reasonable AND that he believes the opposite of me."

True, so long as each is reasonable himself, but that's not a paraphrasing of the theorem, because it exchanges one condition for another.

Even without discussing the evidence available to you about the external world, if each person is reasonable, and if you both discuss merely your conclusions (in light of the private evidence available to you) and confidence in them, and never discuss the evidence itself, you cannot conclude the other person has a different subsequent belief than yours and is rational, provided he correctly assumed you are rational.

Sorry, that doesn't make any sense, and I still don't see any point of disagreement. It does seem like to me that someone else can be correctly applying the canons of deductive and inductive logic to a different body of information than mine and thereby reasonably arriving at some conclusion. That is how Ptolemy came to the rational conclusion that the Earth was at the center of the universe (and not the Sun), afterall.

"Sorry, that doesn't make any sense"

That didn't stop Aumann from earning a Nobel Prize in economics for it (and other work). Maybe I am misstating it, you should look into it. It makes sense to me.

Somewhere a blogger once wrote:

A staggering and unsurpassed amount of work, critical reasoning, skeptical scrutiny, vetting, and aggressive efforts at disconfirmation that have gone into justifying this account of the history of everything. That is, the story is the result of the greatest minds in human history using our best methods for investigating the world.

The arguments that one might make for some other version of events, or the evidence that one might cite to justify a contrary picture of reality, are all inferior. To prefer one of those alternative accounts of reality is, plainly stated, flagrantly irrational.

If that is right, I would recommend rethinking your position. Or if the above wasn't intended to apply to math, game theory, etc., then it applies more broadly.

The study of rationality as rooted in the study of idealized agents, and not in canons of reasoning, explains a lot of things and finds truths the other method missed. I believe it also explains your recent debate with Rauser. Something analogous to this (I can explain more at length later): there is a rule with an exception and an exception to the exception, and you discuss how the rule applies, and Rauser correctly argues that an exception applies, which you deny, and you are right in general because you are intuiting that an exception to the exception applies.

Thanks Brian. Umm, I think I detect more a desire to bicker about something (I'm not sure what) than interest in understanding the position I'm outlining. So I'm not sure I want to keep trying to clarify, esp if those efforts to clarify will just produce more sniping. But maybe I'm reading your tone wrong. The fallibilist view about reasoning and evidence that I've been espousing for years here, is, as far as I can tell, consistent. And it's not an exotic view--it's widely acknowledged by epistemologists and decision theorists. My claim was that your post didn't make sense, partly because of poor writing, not because I'm rejecting Aumann.

I can add this previously unstated assumption to clarify the point about people being flagrantly irrational about The Basics. Given what the mainstream American with a standard K-12, and college education knows, and what she has an epistemic responsibility to know, it is flagrantly irrational to deny The Basics. They should know better, and are epistemically culpable for the denial. Ptolemy, who was not and COULD not be in possession of the relevant information is not similarly epistemically culpable for not accepting the basics. A person's social, historical, and epistemic context relativizes the list of propositions that she ought to accept in order to be rational. But again, this just isn't a controversial position among the experts on the question.

This article gives an account of the recent splits in human populations, and a great diagram that goes with my earlier one

http://io9.com/5944713/the-earliest-split-in-modern-humanity-was-100000-years-ago

Post a Comment